How financial governance not fiscal expansionism remains the key to growth and stability in a world of global financial integration.--Notes from CEDA's Board of Governors Meeting held 20 October 2009.

Paper by Dr Michael Porter presented at the CEDA Board of Governors Meeting, 20 October 2009.

In Brief

The global financial crisis has caused a rethink of fundamentals. This paper, to the contrary, argues that it was a retreat by the finance sector and its apostles from fundamentals that was the problem. But the known workings of a highly integrated financial market need to be respected. In particular:

- That sound and predictable governance, not big government, is the key to human well being;

- That in an integrated financial world we benefit substantially by managing a disciplined financial structure

- That the structure and regulation of financial and labour markets remain the keys to economic performance.

- That with near complete (electronic) financial integration, we and all countries in the market are at risk of contagion when there is a collapse say in the US or other lead economies. This only strengthens the above points.

- This high integration also makes downturns and upturns capable of being more rapid as capital market access turns off and on. The scale of these effects most likely dwarfs Keynesian stimuli, which can make matters worse by crowding out private activity and adding risk.

- That the economic and financial wiz and probability theorist Keynes would not be a "Keynesian" in the 21st century. He would be endorsing classical central banking and attending to fully informed balance sheets and financial transparency.

- That the basis for the Australian economic surge is real - and reflects sustainable growth of China, India and beyond.

- That the mix of Asian growth will reflect extent of change to better governance. The resulting growth will drive Australian exports for decades, as many in the region converge on a levels of income reflective of technology and governance.

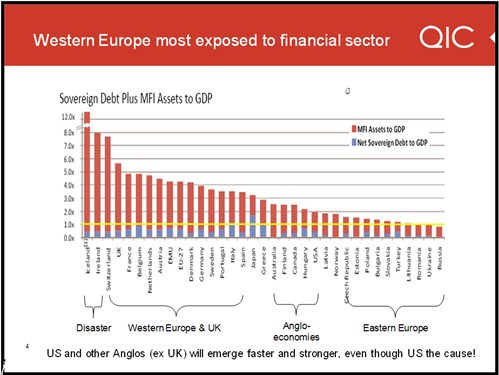

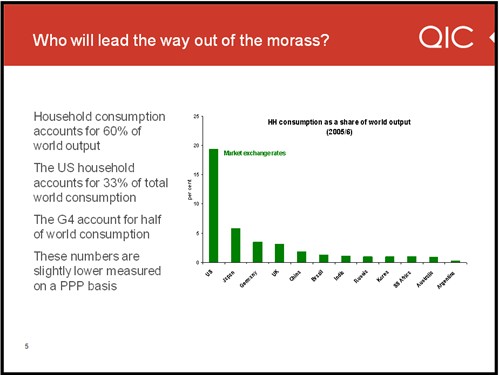

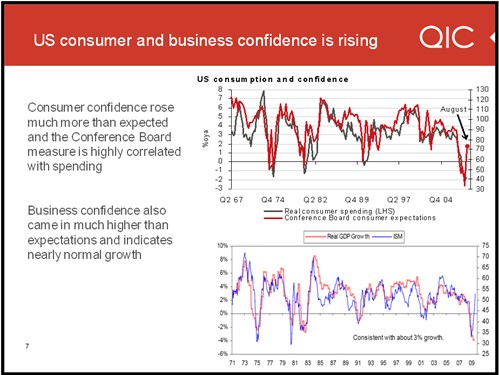

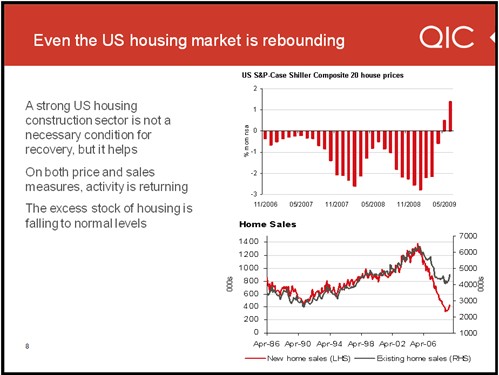

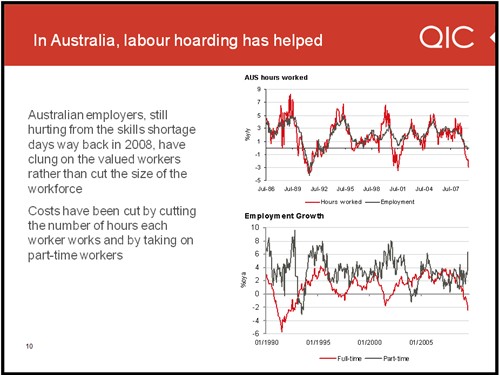

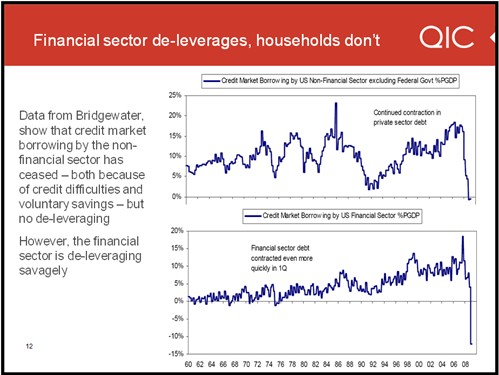

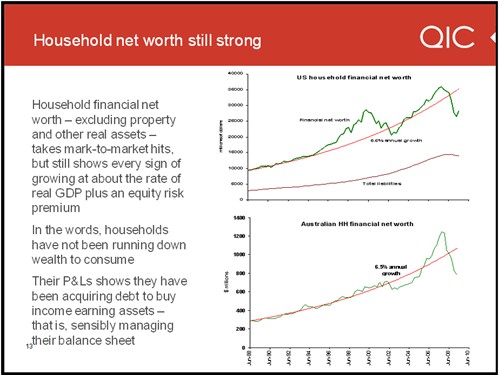

I also attach some annotated graphs of the world and local economic situation courtesy of CEDA Board Member and QIC CEO Doug McTaggart.

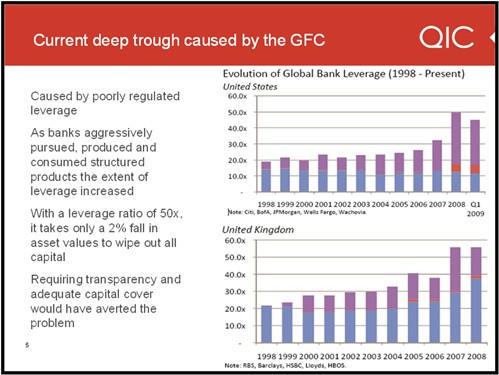

The Finance Opportunity for Australia

The above propositions are far from novel; indeed they ought to be main stream. They can explain not so much the recent failures of economics and finance, but the failure of some forms of governance. Particular targets are economic policies that have force fed funds into US housing for example, and enabled tens of trillions of US$ financial derivatives to be issued against housing finance, but with the details and counterparties neither documented nor monitored. As a result the effective leverage of the banking system expanded beyond reason Pass the parcel has assumed new meanings. So has pass the buck!

Given the bleak performance of both the US and the UK, pursuing sound governance in Australia within a less disciplined external environment can enable Australia to become a wealthy role model and centre of economic, financial and social policy. G1 not G20! That significant leadership role can be underwritten by our vast capacity to deliver needed resources in forms that suit the times; such that Australia should now be entering hitherto unequalled affluence.

Paul Volcker has noted that the US's vulnerability is substantial [1] - and it's all in 3D; (dis)savings, debt and dollars held abroad. At some point the numeraire or reference status of the US dollar will be a problem. The free ride from dollar seignorage will diminish as e-banking expands and as Euro-harmonisation becomes credible, That all means our A$ financial centre capacity will grow, as (or if) the Euro slowly takes hold and as the US dollar weakens.

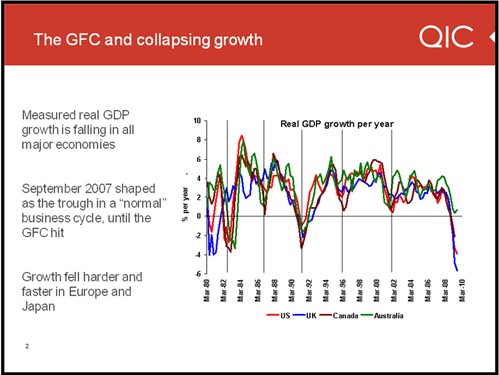

The Global Financial Crisis

The graphs attached to this note, courtesy of QIC, reveal a crash and partial recovery that is remarkably sharp, but uneven. While the US unemployment is now 9.8% and Australia's up to 5.8%, the situation worldwide is greatly varied. But whatever the current state of the economies, this was not a classical drop in demand, not the end of a classical housing boom, not a result of monetary overkill.

This was a financial shock emerging from unsound financing practices in the US. While there was a degree of leverage and debt finance in Australia and elsewhere, that was not particularly unusual and at worst would have led to a "normal" downturn. No, the GFC was leveraged by derivatives in a most unusual and unmonitored way, with the extent of just one derivative, Credit Default Swaps (CDS), on a gross (unmonitored) scale of around US$ 60 trillion, comparable to the world's GDP.

The variability of the bust reflects the varying exposure to US finance and the divergence of local governance. The US mortgage finance industry has constrained the US Congress from legislating sound standards of financial governance, making the US$ and debts as the centrepieces of the world's financial system a real worry.

Greenspan's failure to request or impose any governance arrangements on the derivatives sector is now a matter for apology. But despite Obama intent, a legislated correction is not in place and faces well financed opposition from the sector. A major US problem was the reversal of the institutional separation required by the Glass-Steagall Act, 1933, reflecting a willingness to blur the distinction between banks and non-banks.

As I noted last year, the overlapping and largely unregulated derivative and securitisation activities of US banks, insurance companies, investment "banks", mortgage finance aggregators, brokers, ratings agencies and others created a "house of cards" that would have been avoided under established principles of central banking - e.g. of Walter Bagehot. Instead, words like "credit default swaps" were used to avoid the regulation that would come with the words like "insurance" or "guarantee" - both of which are the core of what constitutes a CDS.

Nothing new in financial integration: remember London Funds?

It needs to be remembered that full financial integration is nothing new; it applies within countries and within and between States and colonies. The notable example is Australia circa 1900 using "London funds" and being in effect part of the London capital market in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Additionally, even in Kalgoorlie in the 1920s-30s, share trading and investment invariably involved futures and virtual derivatives trading.

With hindsight, the principles of sound central banking need to be both reinstated and strengthened, and this means bank access to a discount window that can have extreme elasticity if needed. But we also need differentiation of banks from non-banks such as Lehmans. Lehmans, via its banks, should have had access to lines of credit but with a range of resulting. While bankruptcy has a cleansing effect, the number of corpses that had viable assets was very large.

Runs such as on Bear Stearns and Lehmans are not new and have always been a possibility. Sound central banking and well governed banking systems can handle such collapses. We need across-the-transparent counter documentation of derivatives and the associated counterparties. We need reporting that is full and frank - and not to find there are tens of $ trillions in derivatives of dubious worth and backing.

The speed of collapse and rebirth

The speed with which economic failure or success can be transmitted across integrated capital markets has been shown in the last two years to be very fast. So too the capacity to turn off the taps; to close access to markets and to withdraw lines of credit and other leveraged finance. This all means that while Keynesian stimulus may be warranted at times of unforseen contraction such as at end 2008, the far more important requirement of government is that it ensures the financial system is secure, and that sound projects and borrowers do not have funds turned off for irrelevant external reasons.

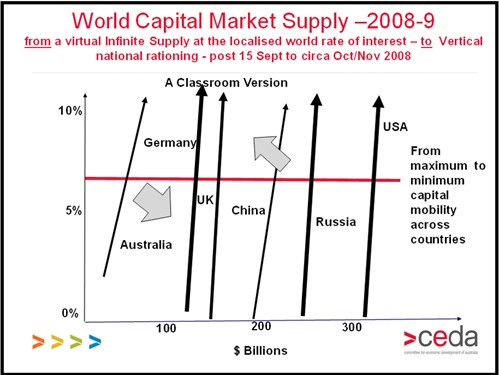

The classroom tools below set out the world of financial integration, wherein there is an almost infinitely elastic supply of capital at the currency and project risk-adjusted rate. Any project can get finance, pre 2008, so long as it meets the criteria. But when the US financial implosion occurs, as at 15 Sept 2008, we see the supply curves shifting from a single world (horizontal) supply function for capital to a domestic autarky or (vertical) local rationing model.

The supply curves of capital country by country became almost vertical as set by Treasuries and Central Banks. Withdrawal of the world capital market as happened in Sep-Oct 2008 meant a collapse towards whatever characterises financial autarky - and if sustained would have been far worse in terms of investment collapse than the great depression.

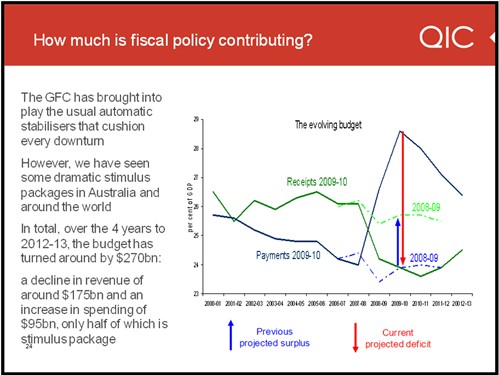

What saved the world I suggest is far more the bank guarantees, the discount windows, and the central banks standing behind the banks looking after sound clients. That's in fact what classical central banking is all about. Setting up huge expenditure programs with minimal vetting, and before unemployment and collapse was confirmed, was not the correct analysis if capital market turnaround could be engendered. But of course if a collapse was to be real then acting early - even the silly example of paying people to dig holes and fill them up to quote Keynes - would have been better than doing nothing to restore the circular flow of income. But we know better than that!

(Figures are for illustrative purposes only)

Other sectoral reforms

While reforms in trade policy, state enterprises, communications energy and transport markets are also areas of relative progress in Australia, it is in how we handle labour and capital markets that largely explains our capacity to benefit from other markets and governance arrangements. In telecommunications, broadband, education, health and transport infrastructure there remains a lingering in Canberra for a larger role for government. The lessons from best practice worldwide however suggest that if we can unlock the keys to best practice in terms of governance in these key social sectors, we will benefit the community far more than financing a "government solution".

In the context of increasingly almost instantaneous linkage between capital markets, the degree of interdependence is extreme. As a result a financial shock from a financial centre such as the US, emanating from housing and derivatives markets, is quickly a matter of concern elsewhere. Thus the state of financial governance at home and abroad is paramaount. In general, capital market integration is a good thing... but we don;t want to be linked to the Mafia, financial disturbances or to those with a capacity for mischief as the internet can potentially facilitate.

Fiscal Stimulus?

Fiscal stimulus has for some time been seen as an increasingly difficulty device for stimulating income, beyond the recipient's income, because of crowding out due to the induced effects on capital markets and exchange rates. The exception here is when countries in concert engage in fiscal stimulus since in that case exchange rate effects tend to wash out.

In my view while keeping the construction sector afloat and restoring some optimism in infrastructure markets has been important, neither of those actions has been of comparable impact to the restoration of confidence, to a lessened degree, in the international financial market.

Governance in other sectors a real constraint

Australian governments continue to sustain a major direct and constraining role in the economy - telecoms, broadband, education, training, health, transport and other infrastructure - rather than optimising the forms of governance for each sector. The success of various innovations around Australia and overseas shows this heavy direction and state ownership is a recipe for missing out on this potential for even further economic progress.

Exactly how such sectors should be governed is of course more controversial and a matter for significant attention at CEDA. But we do know that designing, managing, financing and innovating is not a role in which government has a comparative advantage. Government is better at facilitating structures than running or manning them.

Maintaining a safety net, financing those who need a start or who are in need - that is a central role for government. And note that as with central banking, it is a governance role, not always an expenditure role that is sought.

The China and India Impacts - another governance story

The sustained nature of our growth over the last decade has had much to do with other countries such as China and India gradually moving towards sound economic governance with associated prosperity. These outcomes plus the lessons of poor recent US financial governance and inadequate governance in many Pacific and Asian countries are all showing decisively that "governance not government spending is king" when it comes to creating and growing incomes.

When we view our AusAID budget and priorities it would seem that there is a good fit between Australia promoting sound governance in the region both by aid and example. The countries that have typically done best in the region have had strong economic governance and judicial systems, with those flagging economies typically having weak governance, poor legal systems and endemic corruption.

Epilogue

The lessons of history, distant and recent, all confirm that "it's Good Governance Stupid", to extend the Clinton saying "It's the Economy Stupid". These crystallisations of economic verities reflect answers to questions of why some countries prosper while others collapse. In the long run economic wealth has little to do with physical resources, and even less to do with big government spending.

Big resources and big government can actually crowd out private investment and entrepreneurship if the rules of the game are unsound. And Australia has been doing better than most economies since the 1980s in terms of sound economic governance and arrangements that facilitate wealth creation.

Similarly, in analysing why some countries have ridden through the Global Financial Crisis better than others it's largely a matter of governance, and in particular financial governance in this case.

While exceptions are clear, notably China, the perceived risks and uncertainties in capital markets explain the terms on which countries can obtain or retain capital. When the US mortgage and related financial markets collapsed, this caused a shift from an effectively infinite horizontal supply of capital at the relevant interest rate for each country and project, to a rationed or largely vertical supply of funds - largely through the government and the central bank.

Financial autarchy and capital market protectionism, as each country tends to ration its domestic capital, is far more catastrophic than trade protectionism, since capital is the basis for most investment and thus ongoing employment and growth.

Australia's sound financial and bank governance has restored relatively quickly an elastic supply of funds in Australia, in contrast to a dramatic drying up of funds in many other countries. The guarantee arrangement has also been fundamental in restoring a willingness to borrow and lend. Australian banks got into the World Best 20, and most importantly, investment has fallen by far less than was feared, in large part because lending had been relatively prudent and non-performing loans are around 1.5% in 2009 of total loans c.f. double or treble that level in the UK and US. What has largely explained the strength of the bounce back is not the fiscal spray, but capital market restoration.

[1] "Rethinking the Bright New World of Global Finance" presented in Oct 2007, in the context of the emerging sub-prime housing bust. Source http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/faculty/tambakis/teaching/i%20f%20s/L8%20IF2008%20volcker.pdf